|

John Perlin Author, Lecturer, Consultant — Solar Energy & Forest Preservation Phone: 805.569 2740 • eMail: johnperlin@physics.ucsb.edu |

Godfather of Sol

John Perlin has seen the light —

but is there time for the rest of us?

by Nick Welsh

Santa Barbara News & Review

April 21, 2005

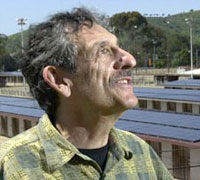

John Perlin is a lot of things. A solar energy expert. A voracious researcher. And a doting father. But more than anything else, John Perlin is a natural-born storyteller; a storyteller of staggering scope and ambition. Perlin's first book - exploring the use of solar energy in antiquity - covered a span of 2,500 years. His second book, A Forest Journey - which Harvard University placed on its list of 100 essential books - synthesized 5,000 years of human history, demonstrating that civilizations rose and fell based on their ability, or failure, to secure timber. By contrast, Perlin's most recent tome - which traces the evolution of photovoltaic solar energy - is a relatively modest undertaking, encompassing a scant 50 years of scientific and technical progress. Up close and personal, Perlin appears to be having way too much fun given the seriousness of his subject matter. At age 56, Perlin rides his bicycle - a green Schwinn Frontier - everywhere. Though his black hair is turning gray, he's blessed with great stamina and he loves to talk. When responding to questions, Perlin tilts back his head, settles deep into his chair, and crosses his muscular legs. He scans the horizon, as if searching for the answer. Then a big goofy grin illuminates his entire face. He's got it.

But often what he's got is pretty scary. In a peculiar way, what unifies all his writings is the one subject Perlin keeps writing around: oil. As a solar advocate - or "guide," as he prefers to be called - Perlin has been arguing the United States' addiction to fossil fuels is self-destructive, shortsighted, economically untenable, and environmentally catastrophic. Given recent events, it's tempting to conclude the world is now in the early death throes of a world order based on petroleum. Worldwide, the demand for oil is accelerating, but new supplies are not being found and existing fields have finite capacity. So far, neither the threat of global warming nor the death of nearly 1,600 U.S. soldiers has generated a national alarm over America's dependence on foreign oil. The United States imports nearly 60 percent of its oil. But the sky-high prices charged at the pump have succeeded in making people mad, while the price per barrel has induced severe sticker shock throughout the stock market. Such economic pain will contribute to the already intense political pressures to open Alaska's Arctic National Wildlife Preserve to new drilling. It will also contribute to mounting pressures to abandon the 25-year moratorium that's protected Santa Barbara's coast from further oil ventures.

In 1982, John Perlin was invited to the United Nations to speak to the delegates about the virtues of solar energy. He was part of a panel that included the Vice President of Exxon, the Vice President of Chase Manhattan Bank, and the chairman of the nuclear industry lobby. Oil, as Perlin points out, is not the only fuel source now dogged by serious problems. The airborne emissions produced by the nation's coal-fired power plants are the single biggest source of the mercury now contaminating America's water supplies. And this summer, when California's air conditioners click on, there may be a serious electricity shortfall from the drought-stricken Pacific Northwest's hydroelectric plants. In just the past four weeks, the nation's nuclear industry has gotten a double-barreled dose of bad news. First, the National Academy of Science issued a report charging the spent-fuel cooling pools of the nation's 78 nuclear plants are far more vulnerable to terrorist attack than previously acknowledged. And revelations of wholesale scientific fraud will further postpone, if not kill outright, plans to open a final resting place for the nation's nuclear wastes at Nevada's Yucca Flats.

Perlin's been down this road before. In a way, he's never left it. During the last energy crisis of the 1970s - and the frenzied cry for increased oil development that unleashed - Perlin first began exploring the potential of solar power. He quickly concluded that the rays from the sun could make a significant contribution to the nation's energy imbalance. But along the way he also discovered that solar was hardly the new, uncharted technology that many in the nation's nascent environmental movement believed it to be. In fact, Perlin found that many of the world's most ancient civilizations availed themselves to solar devices, some quite ingenious and sophisticated. Perlin also discovered that the circumstance prompting these civilizations to pursue solar in the first place was always the same: They ran out of cover wood, which for all but the past few moments of human history has been the second most essential natural resource on the globe - water being the first. In Perlin's worldview, the similarities between wood and oil in planetary importance are decidedly eerie, but hardly coincidental. The paradigm he deduced from wood, he said, applies equally to the petroleum-based world of today. "The equation is plunder, migrate, decline, or adapt," he said. "It's up to us." The good news, Perlin said, is that solar power is so abundant, so adaptable, and so applicable. And lest Planet Earth spin off its axis, it's not ever going to run out. When it comes to solar endowments, few states are as blessed as California, and few regions as abundantly so as the Central Coast, which gets on average 300 sunny days a year. "We're the Persian Gulf of sunshine," said Perlin.

Perlin's been down this road before. In a way, he's never left it. During the last energy crisis of the 1970s - and the frenzied cry for increased oil development that unleashed - Perlin first began exploring the potential of solar power. He quickly concluded that the rays from the sun could make a significant contribution to the nation's energy imbalance. But along the way he also discovered that solar was hardly the new, uncharted technology that many in the nation's nascent environmental movement believed it to be. In fact, Perlin found that many of the world's most ancient civilizations availed themselves to solar devices, some quite ingenious and sophisticated. Perlin also discovered that the circumstance prompting these civilizations to pursue solar in the first place was always the same: They ran out of cover wood, which for all but the past few moments of human history has been the second most essential natural resource on the globe - water being the first. In Perlin's worldview, the similarities between wood and oil in planetary importance are decidedly eerie, but hardly coincidental. The paradigm he deduced from wood, he said, applies equally to the petroleum-based world of today. "The equation is plunder, migrate, decline, or adapt," he said. "It's up to us." The good news, Perlin said, is that solar power is so abundant, so adaptable, and so applicable. And lest Planet Earth spin off its axis, it's not ever going to run out. When it comes to solar endowments, few states are as blessed as California, and few regions as abundantly so as the Central Coast, which gets on average 300 sunny days a year. "We're the Persian Gulf of sunshine," said Perlin.

For most academics, a published opus like Perlin's would be enough to secure lifetime tenure in the ivory tower club or at some prestigious environmental think tank. That Perlin has landed neither, he attributes (with a less-than-apologetic shrug) to his notable lack of social finesse. "Me and my big mouth," he said. As a result, Perlin joins that increasingly rare breed: a scholar without portfolio. But he's paid a high price for his independence. During five of the eight years he spent working on A Forest Journey, Perlin was quasi-homeless, squatting in a camper shell in a friend's Isla Vista backyard. In more recent years, Perlin's been sharing a one-bedroom apartment in San Roque with his 14-year-old son. He gets the couch and his son gets the bedroom. Sometimes he doesn't know where his next check is coming from. In recent months, however, things couldn't be rosier for Perlin: He currently is collaborating with two Nobel Prize-winning UCSB scientists on a documentary film about the history of photovoltaics - and about Albert Einstein's contributions to this budding field. He wrote the narrative upon which the documentary screenplay was based. And A Forest Journey has been so successful that his publishers are releasing a second edition this fall. Perlin just finished writing several new chapters - on the origin of trees and the development of fire - and his publisher has been thrilled. "Things are going good," he said. "I really can't complain."

Native Sun

Perlin grew up in East Los Angeles, the oldest of two boys. His father's grandfather was a costumer for the Bolshoi Ballet and emigrated from Russia around the turn of the last century, fleeing that nation's resurgent anti-Semitism. Perlin's father, Paul, moved from New York at age 18, eventually finding work in Hollywood as a key grip. Both his parents were members of the American Communist Party and his father also was a labor organizer. As a kid, Perlin said he was interested in all kinds of things, from railroads to the stock market to planting watermelon to playing football. But it was a junior high school teacher who urged him to use his evident brain power to get ahead. Academically, Perlin stayed in the top of his class. "You don't get there by yourself," Perlin said. "I had lots of help along the way."

He certainly didn't get much encouragement from his parents. When Perlin wanted to transfer out of Belmont High, which he described as "one of the most violent, mean, and vicious schools in the city," his cover parents were appalled. "They said I was forsaking the working class, that I was an enemy to my class, and that I was trying to kiss up to the man by getting good grades," he said. Perlin transferred anyway. To date, he's the only member of his family to pursue an education past high school.

At age 17, Perlin boarded the Greyhound bus out of East L.A. en route to Santa Barbara to attend UCSB in 1969, back when it was best known for its partying prowess rather than its current academic excellence. But Perlin, then a surfer, found himself drawn by the waves. He signed up for an immense course load. "I didn't go to college with any kind of professional expectation or goals. I just wanted to learn," he said. After graduating, Perlin landed a full fellowship for graduate school at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts. Once there, however, he found himself unimpressed with his professors and decided to travel the world instead. Perlin spent three years in Israel, working on a kibbutz. It was in Jerusalem, riding on a bus in the rain, that Perlin realized he wanted to be a writer, he recalled. In classic Perlin fashion, he hit the books. "I felt I had to read everything in the English language," he said, "and that's what I did for the next five years." He moved to Florence, Italy, where he worked on a farm outside the city. While there, he availed himself to the excellent library at the British Institute of Florence, soaking up as much as he could.

Perlin moved back to Santa Barbara in 1975 and landed a job as a gardener working for Stuart Taylor, then publisher of the Santa Barbara News-Press. When Jimmy Carter was in the White House, gas prices punctured the price ceiling of $1 a gallon. At the time, this constituted a serious affront to America's psyche. While Carter declared energy conservation "the moral equivalent of war," the push also was on for expanded oil exploration and production. That put the oil-rich waters off the Santa Barbara coast squarely in the petroleum industry's crosshairs. But the catastrophic 1969 oil spill, which fouled South Coast beaches and killed thousands of sea birds, remained fresh in environmentalists' memories. Perlin sequestered himself in the library for six months, researching the viability of solar energy. When he emerged, he self-published a pamphlet, The Solar Energy Fact Sheet. It received good reviews, and soon requests for copies were coming in from all over the world. With a few notable exceptions, Perlin believes much of what he wrote then holds up today. "The first thing you have to do is design buildings properly, with energy efficiency in mind," he said. "After that, you can start thinking about renewable energy sources like solar-powered water heaters or photovoltaic roof systems or solar concentrators." In his research, Perlin discovered that as early as the 1890s, many Southern Californians matter-of-factly used passive solar to heat their water, as did ancient Greeks and Romans. This led to the publication of his first book, Let it Shine, in 1980, co-authored with Ken Butti. Sales were decent - though they hardly made Perlin a rich man, and the book drew enthusiastic reviews, and Amory Lovins, the well-known environmentalist/social critic, wrote the foreword.

But it was his discovery that ancient civilizations only began using solar power after they'd decimated their fuel of choice - forest wood - that sent Perlin back to the library. Eight years later, Norton Books published the results of that research in A Forest Journey. The book begins with the Mesopotamians (in what is present-day Iraq), explains how the ancient Athenians went to war against Sparta ostensibly to depose a tyrant but really to secure forest lands, and concludes with the American Civil War, when lumber's importance began to wane as an essential ingredient for global power. This research required Herculean effort. Initially, Perlin camped out in UCSB's Classics Department, collaborating with a professor who helped him research Let it Shine. There, he enjoyed the academic equivalent of Disneyland's E- ticket - an office of his own, secretarial support, full academic access to the UC library system, and use of the pool. And at night, he always found somewhere in the offices to sleep. Perlin insisted on using the primary texts in their original languages. This required considerable assistance. One scholar translated ancient cuneiform tablets from Mesopotamia. "You wonder if the [old tablets] will have some great work of literature, the new Odyssey or Iliad," he mused. "But all it was was a list of receipts. What survives a culture is accounts receivable."

Three years into his research, Perlin and his Classics Department benefactor had a serious falling out over their division of labor. Perlin moved out, losing not just all the academic perks, but the roof over his head, too. Ultimately, he moved in with friends, sleeping in an Isla Vista backyard under a camper shell for five years. To make ends meet, Perlin got a job as a counselor for Let Isla Vista Eat, a now-defunct nonprofit with a checkered reputation. During his years in Santa Barbara, Perlin was befriended by Selma Rubin, an almost irresistible force in progressive political circles and a major supporter of the Community Environmental Council (CEC), one of Santa Barbara's most prestigious environmental think tanks. Rubin, who had known Perlin's father from her days in Los Angeles, took an interest in the young scholar. Thanks to her prodding, CEC created space in the Gildea Resource Center for Perlin to continue his work. Over time, Perlin wore out his welcome. Then Rubin created a small writing space for Perlin in her home and gave him $400 a month. "In the old days, people like John used to have patrons," Rubin said. Perlin, who remains close friends with Rubin to this day, said that without her help, A Forest Journey would never have been written.

When the book was published in 1989, it was greeted by enthusiastic acclaim from scholars and critics alike. After its initial publication by Norton, Harvard University acquired the book's softcover rights in 1991. Since then, the book has sold more than 10,000 copies in five printings. While such figures seem relatively modest, it remains Harvard's number-one bestseller. Shortly before publication of A Forest Journey Perlin began a relationship with Margaret November, an accomplished psychiatrist, and together they had a son, Pesach, now 14. Perlin threw himself into being a father and house-husband with the same intensity with whichn he typically attacks his research. On the Westside, where the family then lived, neighbors remember watching Perlin walk his son to school; the two always seemed to be in intense conversation. His next book, From Space to Earth, the history of solar electricity, was published in 1999, 10 years after A Forest Journey. Perlin, who worked on the book only when his son was at school, experienced first-hand the social isolation and lack of respect child-rearing and housework is afforded. "I was completely shocked," he said. Three years ago, Perlin and his wife split up. Now he shares an apartment with Pesach, who has sprouted into an accomplished weightlifter, wrestler, and Latin scholar. For many years, John Perlin and his son Pesach cut a striking figure walking all over the Westside. They have since moved, and Perlin's son - now 14 - has grown considerably. Here, he demonstrates a nifty wrestling move on his father.

Bright Ideas

While riding the bus several years ago - taking his son back home from a UCSB afterschool program - Perlin struck up a conversation with UCSB professor Walter Kohn, a well-known physicist and Nobel Prize winner. As Kohn recounted, "John has a very strong voice. His son also has quite a strong voice, too. So when they talked the whole bus was part of their conversation." Kohn was thrilled to discover his loud- voiced bus companion was the author of A Forest Journey, which he believes to be "really outstanding and very well written." Over time, a friendship evolved.

About three years ago, they began discussing ways to commemorate the 100th anniversary of 1905 - what's known as Albert Einstein's Year. Einstein, then only 26, published his three famous papers that shook the assumptions of how Western science understood the physical world: one that asserted that light travels both in waves and in particles bordered on scientific heresy. It would take 11 years for it to gain widespread scientific acceptance, but eventually Einstein was awarded the Nobel Prize for his work. For Perlin, this theory has special resonance. Without it, the scientific foundation would not exist for the invention of photovoltaic solar cells. It turns out Kohn was working at Bell Laboratories in New Jersey, where the first photovoltaic cell was "discovered" in 1953. Though he was not working on that project, Kohn remembers the moment well. 'In the United States we have 20, maybe 30 years of great profits to be made on oil. ... We inherited a world with lots of resources, and I don't want my children or your children asking why didn't "those people" do something when they had the chance.'

Because of this, the two decided to celebrate both Einstein's Year and the 50th anniversary of the solar cell simultaneously. Kohn has long been interested in solar energy, but since meeting Perlin, it's become his religion. "In the United States we have 20, maybe 30 years of great profits to be made on oil. I'm over 80 so I won't be here when we run out. But we inherited a world with lots of resources, and I don't want my children or your children asking why didn't 'those people' do something when they had the chance."

Ultimately Kohn and Perlin settled on creating a documentary film fusing the evolution of photovoltaics - which transfer light energy into electricity - with Einstein's theories of light. To this end, they brought in another Nobel Prize winner, Alan Heeger, currently trying to perfect solar cells so thin and malleable they can be manufactured by a printing press. If his technology pans out, it could reduce drastically the cost of solar photovoltaics. That would make them more than competitive with traditional power-plant electricity. Perlin compares his collaboration with Heeger and Kohn to the "three fools" in Sholom Aleichem's short story, "The People of Chelm," who try to collect rays of sunshine and pass them out so the townspeople won't need candles to have light at night.

In this case, the "three fools" have gotten some high-profile help from the likes of UCSB Chancellor Henry Yang and comedian John Cleese, the Montecito resident formerly of Monty Python fame. Yang put Cleese in touch with Kohn. Cleese introduced Kohn to filmmaker Dave Kennard, who produced many episodes of Carl Sagan's famous Cosmos series. If all goes as scheduled, their 55-minute documentary should be available early this fall, along with an educational short.

Power Trips

As to solar's true potential, there's no shortage of debate. Exxon's chief executive has dismissed it outright, while Shell Oil - which has invested heavily in solar - predicts it could meet half of America's energy needs within 80 years. Among renewable energy advocates, there are disagreements, too, as the one between Perlin and the Community Environmental Council. Hoping to do for renewable energy what it did for recycling 25 years ago, CEC has launched an ambitious program to make Ventura, Santa Barbara, and San Luis Obispo counties "Fossil Free by '33." In its just-published Manifesto, CEC projects that far more clean, renewable electricity can be generated by harnessing the ocean's currents than by solar. In addition, CEC anticipates that nearly as much energy can be created by tapping the hair-raising wind tunnels off the Gaviota Coast or the Lompoc Valley as by photovoltaics and solar water heaters. Even if photovoltaics were installed on every rooftop, CEC contends solar could only meet 15 percent of the region's energy needs. "The contribution is small, but significant," said CEC's Tam Hunt. He said the figure could be as high as 25 percent if industrial-scale solar "power towers" were erected. 'If all south-facing rooftops in the United States were equipped with photovoltaics, it would satisfy the electrical needs of this country.'

Perlin begs to differ. But he's not begging politely. At a panel discussion on the future of oil held last November, Perlin blasted the federal Million Solar Roofs campaign - which has been championed by CEC - as "a sham." He said it lacked meaningful funding. That galled CEC executive director Bob Ferris, who was one of Perlin's co-panelists. Ferris and Perlin have since made efforts to kiss and make up. Perlin has apologized for his bluntness, conceding, "I don't think I have the social graces other people have somehow acquired." But he stands by the content of his remarks. "I had lunch with the guy who helped get that program started," Perlin insisted, "and he told me there's no funding." And CEC's Hunt did concede the federal budget for the entire Million Roofs program was only $1 million. That translates to only a buck a roof. As for ocean-current energy, Perlin regards it as "an immature technology" that would be opposed by environmental groups. The same problem, he predicted, would hamper wind energy. "Everyone thinks wind is the biggest alternative at the moment, but solar water heaters worldwide produce five times as much power as wind."

And Perlin discarded the solar "power towers" - more precisely known as "solar concentrators" - as technological dinosaurs. "They only work with totally unobstructed sunlight." Worse, he charged, they require the installation of power lines, which are both costly and lose about 30 percent of the energy they are supposed to carry. "It's ludicrous," he said. "Why would you build this when the world is moving to a more distributive form of energy in which the power is produced right where you need it, namely at your home or wherever?" Perlin is so vehement about "power towers" because in his mind, they violate the very qualities that make solar so superior. For Perlin, photovoltaics are not just some new gadget; he's convinced that quietly, slowly, and irresistibly, photovoltaics will revolutionize the relationship between energy consumer and energy producer. Solar obviates the justification for huge centralized and polluting power plants that harness only a small fraction of the actual energy they create. And they produce energy most at precisely the time demand is most intense - during hot summer months. "If all south-facing rooftops in the United States were equipped with photovoltaics, it would satisfy the electrical needs of this country," he proclaimed. 'Everyone thinks wind is the biggest alternative at the moment, but solar water heaters worldwide produce five times as much power as wind.'

Meter Made

The main impediment to greater solar acceptance is cost. And that is narrowing, while the manufacturing processes to make photovoltaics are improving and the price of oil is steadily increasing. And that doesn't include the subsidies that Perlin claims give oil an unfair advantage. "The Scientific American reported that if you included all the military and diplomatic costs of securing oil into the price at the pump, the cost would double," he said. "And that was before the war with Iraq even started."

If the United States was really serious about solar energy, Perlin said it should steal a page from Gemany's energy plan. There, the government underwrites extremely generous or interest-free loans for homeowners who convert to buy photovoltaics. It also requires utility companies to buy back all excess energy their customers produce and at premium prices. This is called "net metering," and a typical German solar home can make about $1,000 a year this way. As a result, Germany now boasts the fastest-growing PV (photovoltaic) market, as well as one of the most aggressive wind programs in the world. In 2002, Gemany's national energy commission claimed, "It is possible to cover the total energy demand [for Germany] by means of solar/renewable energy sources." While the California Legislature is about to debate a bill requiring homebuilders to include solar-powered options in their home offerings, utility company lobbyists recently tried to kill net metering outright. Although they ultimately failed, they drastically limited the number of customers who can participate.

Where this approach is most obviously counterproductive, Perlin said, is during summer months, when the peak electrical demand overwhelms California's energy grid, causing blackouts and brownouts. If solar energy-producing customers were paid an attractive rate for not draining the grid, Perlin predicts California could avoid a repeat of its infamous 1999 energy crisis. For Perlin, photovoltaics are not just some new gadget; he's convinced that quietly, slowly, and irresistibly, photovoltaics will revolutionize the relationship between energy consumer and energy producer.

But even without net metering and government subsidies, Perlin believes there's much solar can do right now. He pointed out

that all the airstrip landing lights at American military bases - and commercial airports - in Iraq and Afghanistan are solar-powered. "They provide four times better lighting than conventional lights and they are less vulnerable to malfunctioning," he said. (Santa Barbara airport landing-strip lights are conventionally powered.) Likewise, Perlin said, the military now puts solar-powered light-emitting diodes (LEDs) on the security nets surrounding military vessels in foreign waters. The nets, he said, are designed to prevent suicide bombers from attacking American ships; and the solar-powered LEDs are designed to let boat operators where the nets are so they don't run into them. While the Department of Energy seems to be pulling the plug on solar research, Perlin noted that the military has become the biggest supporter. But Perlin suggested the military dropped the ball in one significant way. Had the occupation forces in Iraq used solar power to provide the civilian population with electricity, he said, much of the ill will focused on the United States could have been avoided.

Perlin said while it's important to think globally, there's much that can be done to promote solar locally. In Aspen, Colorado, builders are required by law to design energy efficiency and solar into their plans. Those who choose not to are charged a luxury tax, the proceeds of which are used to subsidize solar retrofits. The Earl Warren Showgrounds earned Perlin's praise for installing large solar panels on the rooftops above the horse stables; likewise, UCSB officials were lauded for installing solar-powered parking meters in Isla Vista and solar-powered lights on the bike path beginning on Modoc Road, where they avoided the costs and hassle of digging underground power lines for each light pole. Other cities, Perlin noted, use solar-powered lights to illuminate their bus shelters and bus schedules. Perlin takes issue with those who discount solar's potential in reducing vehicular oil consumption, which accounts for roughly half of America's oil use. Assuming that many of the cars of the future will be electric or electric-gas hybrids, Perlin suggested that solar panels be installed on the rooves of parking structures. That way motorists could use the sun to recharge their batteries while parked.

Recently, the City of Santa Barbara has adopted a solar-friendly policy - at the instigation of CEC - but it remains to be seen how this will actually shake out. Currently, City Hall is balking at the size of a solar unit now proposed for its downtown library rooftop. While the MarBorg trash company appears to be getting the green light to install a massive array of solar panels on its new garbage processing facility, many environmentalists feel City Hall did not push hard enough to get solar components included in the design of the expanded Cottage Hospital or the brand-new $20 million Granada Parking Lot. In North County, which boasts some of the best sunscapes in the state, interest in solar energy is growing, instigated more by economic considerations rather than environmental virtue. Some farmers - under regulatory pressure to cut diesel emissions from the water pumps used to irrigate their fields - have formed a company to manufacture and sell solar-powered pumps.

Private industry is getting involved too. The Santa Barbara County Federal Credit Union - which itself is solar-powered - is offering low- interest loans for people seeking to buy photovoltaic systems. And the head of the Santa Barbara Building Council, Joe Campanelli, happens to be one of the biggest solar boosters around. And while home photovoltaic systems remain somewhat pricey, large businesses have figured out how to simplify them and sell them to do-it-yourself home improvers at big-box outlets like Costco. Perlin understands that for many people already hooked into the grid, the cost of photovoltaics still remains prohibitive. He's confident that as solar technologies improve, costs will drop. But Perlin has his eye on an even bigger prize. "Hey, there are more than two billion people in the world who don't have any electricity at all right now," he said. "They're not hooked into the grid. Now is the time to make sure they never do."

© Copyright 2000 - 2020 All rights Reserved John Perlin